Quantum field

- A field itself, either in classical physics or in its quantization, is simply a function on spacetime, assigning to each spacetime point the "value" of that field at that point. Or rather, more generally it is a section of a bundle over spacetime manifold.

- In case of a quantum field, the field operators $\phi(x)$ at different spacetime points $x$ are different operators, but they all act on the same underlying Hilbert space.

- There is a single, fixed Hilbert space of states, on which all the operators $\phi(x)$ act, not a different Hilbert space for each $x$. The Hilbert space in question is usually a Fock space, which is a direct sum of tensor product spaces, each one corresponding to a certain number of particles. The Hilbert space provides the "stage" on which all these operators act, and it's constructed to be rich enough to accommodate all the phenomena we wish to describe, such as particle interactions, creation, and annihilation.

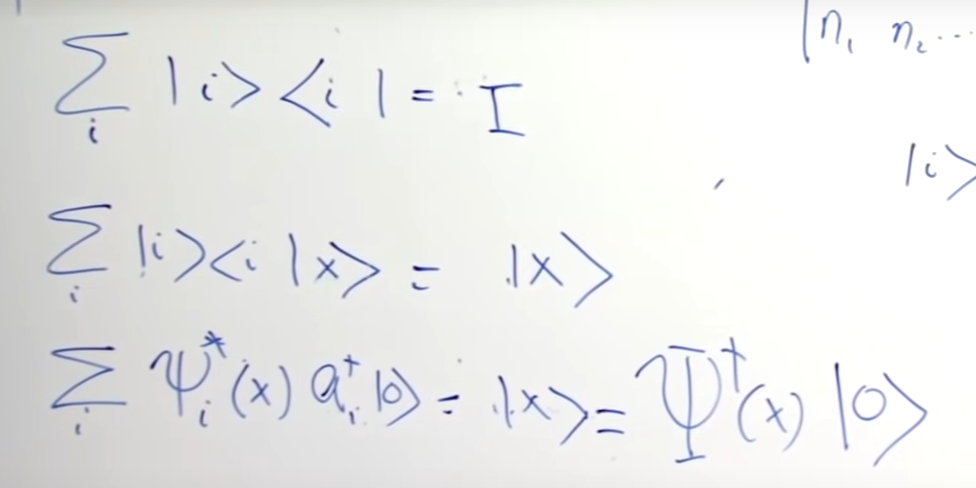

- According to Susskind (here and better here, a quantum field is a linear combination

where:

- $\{|\psi_i\rangle\}$ is an orthonormal basis of eigenstates for the Hamiltonian $\hat{H}$ of a certain 1-particle system.

- $\psi_i(x)=\langle x|\psi_i\rangle$ are the wavefunctions of these states

- $a_i^{-}$ is the annihilation operator which operates on the Fock space.

According to this derivation of Susskind

the quantum field or, better said, its Hermitean conjugate $\Psi^{\dagger}(x)$, when applied to the empty state $|0\rangle$, it creates a single particle localized at position $x$.

Similarly,

$$ \Psi^{\dagger}(y)\Psi^{\dagger}(x)|0\rangle $$is a two particle state, one at $x$ and one at $y$.

Moreover, here Susskind shows that $\int dx \Psi^{\dagger}(x)\Psi(x)=\sum_i N_i$, where $N_i$ is the number operator. So this integral represents an operator which gives us, when applied to a state, the total number of particles. Therefore, $\Psi^{\dagger}(x)\Psi(x)$ represents the "particle density", and it can be measured. Indeed, it is $\int_R dx \Psi^{\dagger}(x)\Psi(x)$, with $R$ a small region of space, what can be measured.

Also, he shows that in case that $\omega_i$ is the eigenvalue associated to $\psi_i$, then

$$ \hat{E}:=\int dx \Psi^{\dagger}(x)\hat{H}\Psi(x)=\sum_i N_i\omega_1 $$where $\hat{H}$ is the Hamiltonian of the 1-particle system. So the operator $\hat{E}$ is the Hamiltonian of the quantum field theory.

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author of the notes: Antonio J. Pan-Collantes

INDEX: